Why won't you DIE? IBM's S/360 and its legacy at 50

Big Blue's big $5m bet adjusted, modified, reduced, back for more

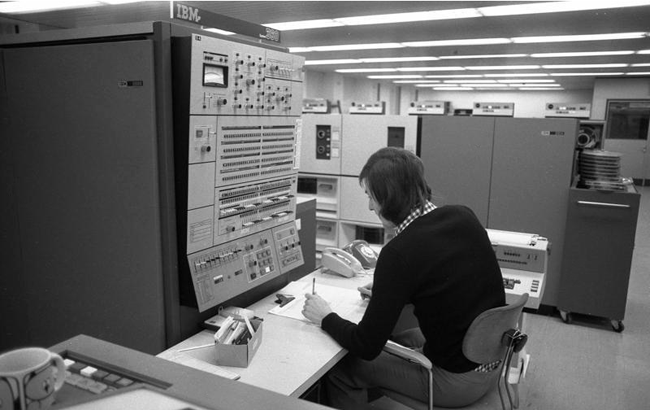

IBM's System 360 mainframe, celebrating its 50th anniversary on Monday, was more than a just another computer.

The S/360 changed IBM just as it changed computing and the technology industry.

The digital computers that were to become known as mainframes were already being sold by companies during the 1950s and 1960s - so the S/360 wasn't a first.

Where the S/360 was different was that it introduced a brand-new way of thinking about how computers could and should be built and used.

The S/360 made computing affordable and practical - relatively speaking. We're not talking the personal computer revolution of the 1980s, but it was a step.

The secret was a modern system: a new architecture and design that allowed the manufacturer - IBM - to churn out S/360s at relatively low cost.

This had the more important effect of turning mainframes into a scalable and profitable business for IBM, thereby creating a mass market.

The S/360 democratised computing, taking it out of the hands of government and universities and putting its power in the hands of many ordinary businesses.

The birth of IBM's mainframe was made all the more remarkable given making the machine required not just a new way of thinking but a new way of manufacturing. The S/360 produced a corporate and a mental restructuring of IBM, turning it into the computing giant we have today.

The S/360 also introduced new technologies, such as IBM's Solid Logic Technology (SLT) in 1964 that meant a faster and a much smaller machine than what was coming from the competition of the time.

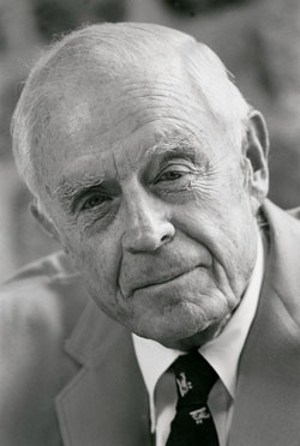

Thomas J Watson Jr - in the hot seat when the S/360 was born

Big Blue introduced new concepts and de facto standards with us now: virtualisation - the toast of cloud computing on the PC and distributed x86 server that succeeded the mainframe - and the 8-bit byte over the 6-bit byte.

The S/360 helped IBM see off a rising tide of competitors such that by the 1970s, rivals were dismissively known as "the BUNCH" or the dwarves. Success was a mixed blessing for IBM, which got in trouble with US regulators for being "too" successful and spent a decade fighting a government anti-trust law suit over the mainframe business.

The legacy of the S/360 is with us today, outside of IBM and the technology sector.

Bankers' delight... unless you're RBS

Banks, insurance companies, retailers and power companies - the great and the familiar from the City mile to the high street run many operations on an IBM mainframe: RBS, Nationwide, EDF, Scottish Power, Sainsbury's, Tesco and John Lewis. There's the Met Office and Land Registry, too.

Ninety-six of the world's top 100 banks run the S/360 descendants with mainframes processing roughly 30 billion transactions per day.

These transactions include most major credit card and stock market actions and money transfers, manufacturing processes and ERP systems.

If you want a testament to the sustained power of the mainframe then look at RBS. Two years ago, a simple human error on the part of those running RBS's mainframe crippled the company's core business. Sixteen million customers were locked out of their accounts for days, unable to withdraw money or pay in.

These accounts were housed, as they are in many banks, on the mainframe at the banking group's corporate and technology HQ in Edinburgh.

Lessons learned

Fifty years after the first S/360 was announced and 30 years after the rise of distributed systems that were supposed to replace them, the mainframe is smaller in market share, but its principles are being embraced once again.

Google and Facebook run tens of thousands of distributed x86 servers but these servers are clustered, use fast networking and virtualisation and are managed centrally to ensure near-continuous uptime of mission-critical tasks.

Searches on Google and status updates on Facebook are the new mission-critical: back in the day a "mission critical" was ERP and payroll.

Further, there has been an uptick in the mainframe business for IBM - more servers and more processing are being bought. Meanwhile, IBM has released new mainframe servers – and not just for the old guard: it's targeting cloud startups.

With so many core business apps sitting on mainframes, mobile computing is making it even more important to what companies are doing.

CIOs now predict they will depend on the mainframe for least another decade, while 89 per cent reckon their mainframes are running new and different workloads to those they ran five years ago, in 2009. Mobile computing is the driver, as companies' customers want to access accounts and information held on those legacy systems.

2009, if you remember, was the year after the first iPhone and Android phones from Apple and Google's partners were released... and just one year before the first iPad was released.

Along with the mainframe's renewed success there have been problems: dependency, as well as a shortage in staffers qualified to run or maintain them.

Compuware tells us of a large number of support calls it receives are from those who simply don't know how to install new software on a mainframe.

The consequences can, and have, been disastrous – as RBS proved.

The same Compuware survey that found CIOs' reckon the mainframe will be critical to their business over the next decade also found that the tech chiefs were fearful.

Guess who's back?

That resurgence was somewhat surprising for something that was intended as nothing more than a 10-year product roadmap for a company that had seemed to be running out of steam. There was nothing inevitable about the business that grew from the S/360. In fact, Fortune in 1966 called it (PDF) IBM's $5bn gamble - the amount the S/360 finally cost IBM to deliver.

And no wonder: the S/360 had gone more than $4bn over budget - it had been initially estimated by IBM's beancounters in 1962 to cost $675m.

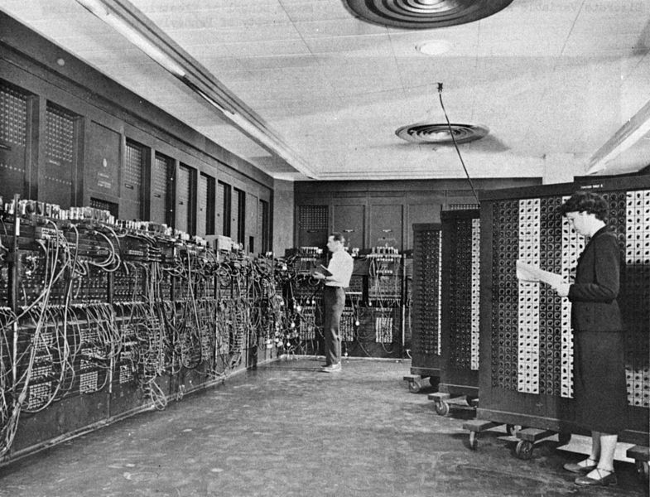

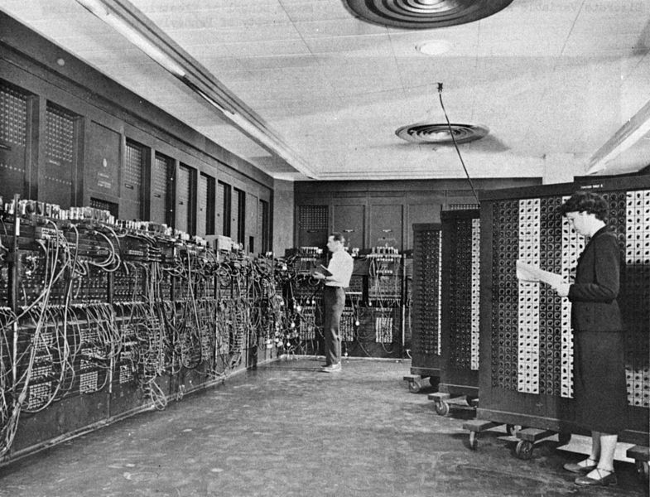

ENIAC: 18,000 square feet and 30 tones of computer

IBM – first incorporated back in 1911 as the Computing Tabulating Recording Company – entered the 20th century making and selling tabulators and punch cards along with a range of lesser business equipment that included meat and cheese slicers.

The 1930s and 1940s saw government, academics and businesses start to build their digital computers to crunch large volumes of data more quickly than could be done using the prevailing model of the time: a human being armed with a calculator.

The 1930s and 1940s saw government, academics and businesses start to build their digital computers to crunch large volumes of data more quickly than could be done using the prevailing model of the time: a human being armed with a calculator.

Big names from the era included ENIAC - the Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer - used by the US army to calculate missile firing ranges in 1946. ENIAC used 17,468 vacuum tubes for switching and computation, and was capable of 5,000 additions, 357 multiplications and 38 divisions in one second. It was also big - 18,000ft2 and weighing 30 tonnes, it took an all-female team of mathematicians weeks to program ENIAC's system for jobs – and it cost a whopping $500,000 to build.

In the UK we had the Electronic Delay Storage Automatic Calculator (EDSAC), which ran its first programs in 1949. It was a stored-program system with 3,000 valves and magnetic tape backup and storage. EDSAC paved the way to LEO - the Lyons Electronic Office - the world's first business computer. And there were others.

The business that broke the bank

IBM had been moving into data-processing, too, and it had a variety of systems that used vacuum tubes and transistors. Business was brisk.

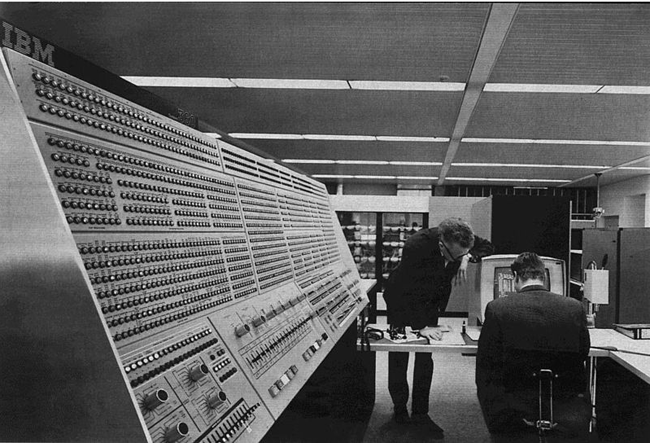

But IBM wasn't alone and others were moving into computers: Honeywell, Burroughs and Control Data Corp. Notable among rivals was Remington Rand: its machine, the UNIVAC 1, had successfully calculated the winner of the US presidential election on TV on the evening of 4 November, 1952.

The real killer was the fact that the UNIVAC 1 came from two of brains behind ENIAC itself: J Presper Eckert and John Mauchly, who'd gone into business as the Eckert-Mauchly Computer Corporation. They'd started the UNIVAC 1 as a project for the US Census Bureau on an initial deposit of $400,000 in 1951. But the project broke them, and they sold to Remington Rand, famous for typewriters and razors, who completed the UNIVAC 1 at a cost of $1m.

A UNIVAC with its co-creator J. Presper Eckert

(center) and US TV reporter and anchor Walter Cronkite (right)

UNIVAC 1 was smaller than ENIAC, just 5,200 vacuum tubes, and faster with an addition time of 120 milliseconds, multiplication time of 1,800 milliseconds, and division time of 3,600 milliseconds. It was relatively easy to program, too.

Revenue in 1962 was $2bn, up from $4m in 1914. But growing competition was making IBM look like just another computer company and people were starting to think company's best days were behind it and its growth had plateaued.

IBM wasn't helping itself either. The company was saddled with supporting and developing a diverse set of non-compatible products for both high- and low-end needs that were all very much single-purpose machines.

Making things worse, IBM engineers had been busy on custom mainframes. These included the Naval Ordnance Research Calculator (NORC) and SAGE (Semi-Automatic Ground Environment) AN/FSQ-7 family of networked systems used in US air defence.

And by the early 1960s, IBM was planning on adding yet another system to the already complex mix - the 8000, which it was calling "a massively powerful super computer".

Middle-aged SPREAD

Under a relatively new CEO - Thomas J Watson Jnr - IBM management convened a special committee in autumn 1961 to evaluate the company's operations. Named SPREAD, the committee's name stood for Systems Programming, Research Engineering and Development. There were no sacred cows: everything IBM was doing with computers and peripherals was to be examined to determine product and development direction for the next 10 years.

The 80-page report was delivered by Christmas. In short, it recommended a range of five scalable systems varying only in processing power, with the largest being 200 times more powerful than the first, and each device designed to be compatible with the others. The idea was for a program that ran on one could run on all systems and that all computers would use standard interfaces - nothing custom.

The processors must have new capabilities not present in existing IBM computers the new family would not be compatible with IBM's existing systems.

Watson wasn't sure about what he was about to undertake.

S/360 arrives

The System 360 "was the biggest, riskiest decision I ever made, and I agonized about it for weeks, but deep down I believed there was nothing IBM couldn't do," he wrote in his memoirs, Father, Son and Co: My Life at IBM and Beyond.

What emerged from SPREAD was a family of six compatible machines - the S/360 30, 40, 50, 60, 62 and 70, which Watson Jnr announced on 6 April, 1964.

The S/360 was remarkable for a number of conceptual and technological reasons. First, it separated design from build, so systems could be replicated. This allowed components to be specced and manufactured using a standard process, ensuring the S/360 wasn't a one-off or relatively custom build that was hard to turn into a successful business - like UNIVAC.

Part and parcel of this was the "compatible" moniker of the S/360. IBM built what today might be called a plug-and-play stack: that is, all components from circuits to memory, storage, printers and screens were designed and manufactured by IBM.

The parts' compatibility made the S/360 modular: Watson Jnr announced six systems but they came in 19 combinations of power, speed and memory size. The smallest was capable of 33,000 additions per second and the biggest 750,000. A total of 54 peripherals were also available from IBM: from magnetic storage devices and visual display units to printers, card punches and more.

The benefit for IBM was a system that was relatively low-cost to make and easy to customise to meet a relatively broad number of customer scenarios.

Also, the hardware was separate from the software program and the program could - in theory at least - run on difference versions of the S/360. The plug-and-play nature of the hardware side thus extended to the software.

This was, in truth, one of the hardest parts of the dream to deliver: IBM struggled to make the operating systems and the apps run on different sized S/360s and to make the underlying operating systems capable of being multi-function.

Flash-Gordon tech - vacuum tubes, once the state of the art

As a mainframe, the S/360 wasn't a new beast. What IBM did succeed in doing was bringing the manufacturing, technical specification and use of such systems into what we might call the modern age. The S/360 changed the face of what had been at best a cottage and at worst Heath-Robinson industry: it turned making mainframes in to a Henry-Ford-style, large-scale manufacturing process.

Machines finally evolved from the era of Flash-Gordon-esque vacuum tube processors – from looking like light bulbs that were state of the art in the 1930s and 1940 to looking more in sync with the integrated electronics era of the post-war world.

The S/360 introduced new IBM technology, it found a use for existing IBM technologies, and it embraced new thinking in the industry.

Good things come in small(er) boxes

IBM built its own circuits for S/360, Solid Logic Technology (SLT) - a set of transistors and diodes mounted on a circuit twenty-eight-thousandths of a square inch and protected by a film of glass just sixty-millionths of an inch thick. The SLT was 10 times more dense the technology of its day.

IBM built its own plant to manufacture the SLTs at a site in East Fishkill in the Hudson Valley, and by 1965 was making 28 million to keep up with demand. It built so many that 25 per cent failed quality control. Years later, East Fishkill became a major IBM chip manufacturing plant.

Memory in the S/360 was standardised on something new called magnetic core. A variety of technologies had been in use by different computer companies, including IBM. These included large and bulky drums filled with mercury through which electronic pulses were sent and amplified, cathode ray and thin-film memory. None were 100 per cent reliable and all had their problems.

Magnetic core was new, and it was digital: a set of tiny doughnut-shaped metal circles in a wire honeycomb that would be magnetised and stored zeros and ones.

The S/360 Model 91 at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center, with 2,097,152 bytes of main memory, was announced in 1968

Storage was via a disk drive, the IBM 2311 that looked like an old-style, top-loaded washing machine or spin dryer. The 2311 stored up to 7.25MB on a single, removable disk and came with an IBM-standard interface.

Not everything was invented for the S/360 or came from IBM. Disk storage dated from IBM's 305 REMAC - Random Access Method of Accounting and Control machine - in 1956. COBOL - a staple of mainframe applications - dated from 1959 and was based on the work of ENIAC and UNIVAC programmer Grace Hopper.

The software

Nothing is simple in IT and dreams never arrive as predicted, and so it was with the S/360.

Building the software was one of IBM's biggest headaches. Developing and delivering the S/360 cost $5bn, not the $675m IBM estimated it would in 1962. Of this, $4.5bn went on new facilities like East Fishkill and on buying and renting equipment.

Of the remainder, software was the single biggest hit. The cost had been estimated to come in at $30m and $40m. The final number was $500m.

The problems were numerous and saw the Operating System 360 go months late. Among the challenges were making new innovations work together and making the system upwards-compatible and able to run two or more programs simultaneously and also take inputs from more than one different users.

A thousand engineers toiled to eventually produce one million lines of code.

Even upon completion, not not everything worked exactly as envisaged. Model 20 was not binary-compatible with rest of the range. Neither was there a single operating system: there was Basic Operating System/360, Tape Operating System/360 and Disk Operating System/360 for the three low-end machines and the Operating System/360, Primary Control Program and Multiprogramming with a Fixed number of Tasks (MFT) for the higher end systems.

Also, time-sharing didn't arrive until the S/360-67, announced in 1965 and not delivered until 1967 – IBM had preferred batch processing.

For the customer, though, the S/360 was a success. It meant large-scale computing power was something businesses could do more than just run their business on, they could run new business, too. The S/360 was a multi-purpose rather than a one-user product suited to just a single function. Up to 248 data transmission terminals could communicate with the computer, even when it was busy on a batch job. It was not only capable of working on small binary, decimal or floating-point calculations, it could also process scientific and/or commercial jobs.

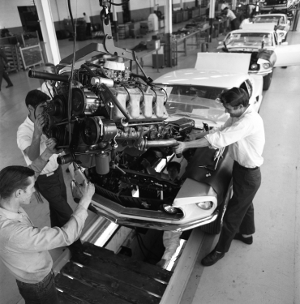

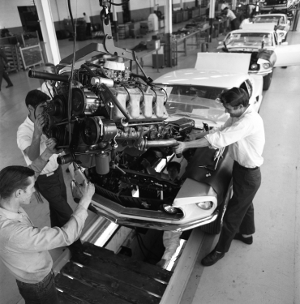

Early adopters included the Ford Motor Company, which was able to introduce a warranty system and a retail loan system using its S/360.

If you couldn't buy, you could rent: monthly prices started at $2,700 for a "basic" configuration and up to $115,000 for a "typical" large multi-system.

Before the S/360, memory and storage were in short supply and expensive to add. The S/360 gave large and relatively unlimited volumes that were easy to slot in, with a central memory capacity of 8,000 to 524,000 characters.

The $5bn gamble paid off. By the end of 1966, around 8,000 S/360s had been built and installed. Compare that to 46 UNIVAC 1s and 36 UNIVAC 1107s.

IBM revenue had nearly doubled to around $4bn and by 1970 it nearly doubled again to $7bn. It was also hiring to keep up with demand – taking on 25,000 staff by the end of 1966. By 1970 staffing levels had gone from 120,000 in the pre S/360 age to 269,000.

NASA's Apollo 11 Capcom team who got the first men back from the moon using an S/360.

NASA's Apollo 11 Capcom team who got the first men back from the moon using an S/360.

As it entered the 1970s, IBM claimed 70 per cent of the world's mainframe market – with customers including Ford, Volkswagen McDonnell Aircraft Corporation and NASA. On the latter, a total of five S/360s had helped run the Apollo space programme, with one of IBM's mainframes being used to calculate the data for the return flight of Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin and Michael Collins - the team that put boots on the Moon for the first time.

By the late 1960s and early 1970s, the original S/360s were being replaced by newer mainframes, but the momentum had carried IBM through the decade.

IBM was so far ahead of the competition, observers began to brand it the Seven Dwarfs or the BUNCH. This moniker referred Burroughs and Univac - which merged to create Unisys in the 1980s; Control Data Corp (CDC); General Electric, which sold its business to Honeywell; and NCR and RCA.

IBM's lead was too much for some in the US government, though. The US Department of Justice (DoJ) began antitrust proceedings in 1969, alleging IBM was operating an illegal monopoly in the mainframe market.

Lights out by 1997. Not quite.

The DoJ said IBM had eliminated competitors using the price of its machines, software and services and by through the use of bundling. It wasn't until 1982 that the DoJ dropped its suit, when IBM's market share had fallen to 62 per cent and a new computing power was in the ascendancy - the personal computer.

The original six S/360s were succeeded by newer models and eventually the S/360 line by the S/390 and zSeries. The rise of the x86 PC and server bred a belief about the "inevitability" of the death of the mainframe. Typifying these was venture capitalist and former editor-in-chief of InfoWorld Stewart Alsop, who in 1991 said: "I predict that the last mainframe will be unplugged on March 15, 1996."

The original six S/360s were succeeded by newer models and eventually the S/360 line by the S/390 and zSeries. The rise of the x86 PC and server bred a belief about the "inevitability" of the death of the mainframe. Typifying these was venture capitalist and former editor-in-chief of InfoWorld Stewart Alsop, who in 1991 said: "I predict that the last mainframe will be unplugged on March 15, 1996."

Yes, mainframes have been turned off. NASA, one of the first on S/360, turned off its last Z machine in February 2012. Long-time mainframe shop Amadeus, the travel booking hub used by airlines and hotels, turns off its last mainframe this year.

Ford spun up brand-new business lines thanks to IBM

Mainframe sales, like market share, have fallen, and IBM is ruler of a reduced kingdom. The worldwide market for Complex Instruction Set Computing (CISC) - the architecture used in mainframes - was worth $5bn in 2013 versus $48bn for other CPUs, according to IDC. IBM holds 81 per cent of that market.

But while S/360 is gone, its descendants are holding on. With mainframes running critical functions and holding so much data that's vital to businesses and customers, turning off that last mainframe has proved an impossible task.

In fact, the mainframe has been enjoying something of a renaissance thanks to mobile computing the web and cloud.

The ability to book travel online or access your bank account through a smartphone have seen consumption of MIPs - millions of instructions per second used to measure mainframe computing - grow by an average of 41 per cent, according to data from Compuware. Eighty-one per cent of CIOs believe the mainframe will remain a "key" business asset for another 10 years,

IBM's Customer Information Control System (CICS) is the application server/operating system used to manage transactions on mainframes; 70 per cent of mainframe shops plan to expose their CICS systems to the web, according to a 2013 Arcati study last year. IBM's DB2 database and IMS on the mainframe are going the same way.

IBM senses a fresh opportunity.

Sales of the mainframe might be a shadow of what they were, but they are stable - around $5bn year each year since 2009 says IDC, down from $6bn in 2008. The difference was the 2008 economic crash, when banks cut their IT budgets.

IBM has been marrying that to two trends and use cases: cloud servers and analytics engines and bread-and-butter business servers in the enterprise.

The cloud is a significant departure to the past, given this has been the preserve of distributed x86, with companies like Google, Facebook and Twitter packing tens of thousands of branded and custom x86 boxes into vast data centres.

IBM has delivered the BC12 zEnterprise capable of running 520 virtual Linux servers at a claimed cost of $1 a day. IBM also bought SL International for virtualisation management on the zEnterprise for $20m - IBM's first act of mainframe M&A since Platform Solutions in 2008 to run zOS on non-IBM hardware.

We asked to speak to a mainframe customer, and rather than a traditional bank or airline, IBM gave us a nine-month-old cloud startup - L3C, which is running the BC12. L3C is IBM's newest mainframe customer, buying its BC12 in December 2013.

L3C's business is part infrastructure, part software-as-a-service: it offers mainframe-as-a-service for others, hosting Oracle database software, e-commerce and CRM hosting, and virtual machines for dev, test and deployment. Target customers are telcos, banks and financial services and IT companies.

Managing director and founding partner Lubomir Cheytanov said he went mainframe rather than x86 for reasons of cost and management.

While the BC12 is more expensive up front than the average x86 server, starting at $75,000, Cheytanov reckons he can save by the fact he can pack in more virtual machines on the server than on the average Intel blade. This will save on physical space, power and cooling while the job of administering by a human will be simpler because the mainframe is more reliable - again helping save on costs.

"I will be a lucky man if I have to put a second [BC12] in," said Cheytanov – referring to the huge amount of scale provided in his new mainframe.

Given one year and just 20 paying customers, Cheytanov reckons he could soon be cash-flow positive and have recouped his initial outlay.

Arguably, IBM's best move for the mainframe was putting Linux on the System Z mainframe descendants of the S/390. Jose Castano, IBM director for System Z, claimed more than 70 new clients, with most - 60 per cent - using Linux. The Linux-on-mainframe business is growing at a compound annual growth rate of 30 per cent, he said but wouldn't break out actual numbers.

On the other end of the spectrum are the mainframe old guard: banks, financial institutions and public sector, expanding consumption or buying brand new.

You can bank on it

RBS is an example of one customer buying more - spending £450m on brand new mainframe and estate at the HQ in Edinburgh to make up for the 2012 outage. Others, like Nationwide, are consolidating data centre ops, Castano said. Still others have been starting up new operations on mainframes, rather than going x86. Banks in emerging markets like China, where mainframes sales have grown, have gone Z-series during the last 10 years and upgraded as IBM has released new products.

Castano, meanwhile, also reckoned on another category of enterprise use: those running analytics and serving up Java applications on their zOS.

IBM was catering to this market when it released the zEnterprise EC12 in 2012. The child of a $1bn R&D effort, the machine offers 25 per cent better performance and 50 per cent more capacity than its predecessor, Big Blue claims, with 100 configurable cores. It has also created mainframe configurations that work with x87 and Power blades.

Why would customers, even those starting from scratch, go mainframe – apart from the performance or ROI factor? IDC server and cloud research manager Giorgio Nebuloni points to the roadmap. Now, just as in 1964, IBM offers something you can bet on over the long term.

Nebuloni said: "IBM have been very clever in that they didn't just monetise the mainframe - they created a platform for the customer and said: 'You have critical applications on this. We promise you, we will support you. We have roadmaps spanning five to 10 years. If you are around in 10 years we will be there to support you'."

Indeed, IBM does seem rather committed to the mainframe. Fifty years after the S/360, it was IBM's x86 servers business that had been sold, not the legacy mainframe unit – despite the fact that it was x86, the distributed server, which was supposed to be the future. The sale followed the selling of the x86 PC business in 2005. Both have gone to Lenovo.

Why would IBM keep one and not the other? One reason could be profit margin. Margins on x86 servers run between 15 and 30 per cent but on mainframes and Unix it's more than 50 per cent. The revenue mostly comes from the sale of software licences. IBM dumped the PC business because it couldn't make a decent profit on that either.

Ford rival Volkswagen shared common ground on love of the S/360

What's next? The BC12 provides a peek into the future of where IBM is looking, Castano says. He promised more work on speed via threads and with more bandwidth on the processor; he also said Big Blue would work on acceleration to speed apps without relying on just the processor. There will be more work on solid-state drives, analysis of machine data, and support of open standards – especially in virtualisation.

Castano claims cloud is the re-incarnation of the mainframe service bureau and concepts such as virtualisation, metering and automation are concepts the world of distributed systems has only now realised it needs to catch up with. Plenty would agree.

And yet the picture is more complicated.

Watson's gamble certainly paid off for IBM and for the industry. What was perceived as a simple 10-year survival plan became a blueprint for IBM and for building computers as a whole - not just other mainframes but later PCs, too.

But let's not get too hagiographic. The S/360 wasn't a new idea, rather a successful intersection of new and emerging technologies.

What came with it was the industrialisation of computer manufacture on a grand scale to satiate demand and create the first mass market for computers. IBM did what American companies do best: manufacture and sell at scale.

Further, the legacy of the S/360 is still with us. Unlike some systems already forgotten or behind glass in a museum, the mainframe become so important to critical segments of society that they cannot be switched off.

And thanks to our appetite for Linux in the cloud and for web-scale computing, IBM's found a fresh outlet for a system that runs counter to everything we are told computing is today: cheap, open and a commodity. The mainframe is expensive and, at its core, it is also proprietary.

On the 50th anniversary, should we expect just one more decade for the mainframe as some CIOs are now saying? Will it be lights out in 2024?